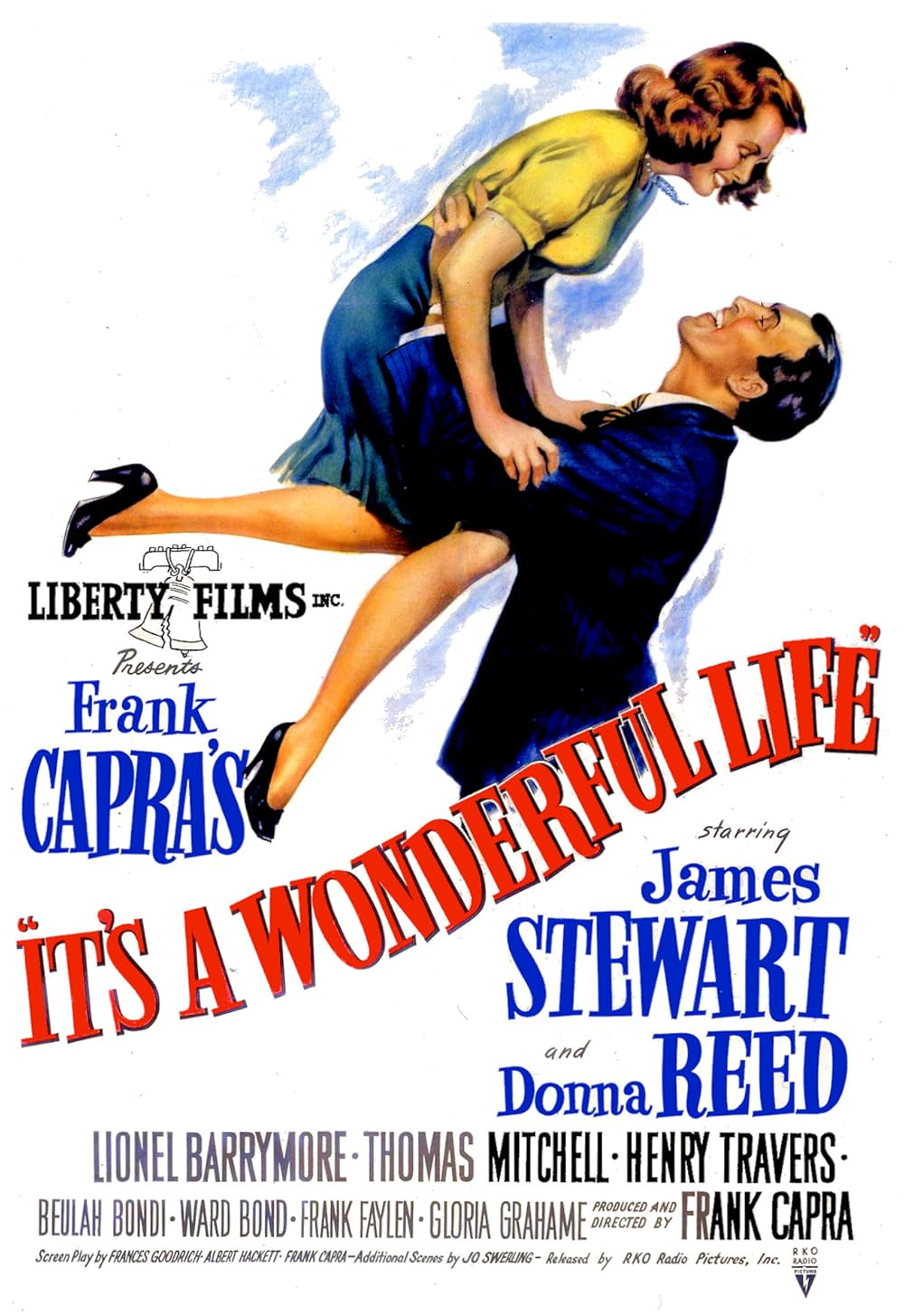

Reader, it’s officially the most wonderful time of the year. Your friends, your family, and your coworkers are all rewatching It’s a Wonderful Life, or at least thinking about rewatching It’s a Wonderful Life. And why not? It’s a beloved film that celebrates the real reason for the season: college football.

No, there aren’t any scenes that take place at a football game. There aren’t any characters who casually toss the pigskin around. There isn’t even a television set with a football game on. But It’s a Wonderful Life is a football movie because of two short sentences spoken by a senior angel up in the heavens: “Harry became a football star. Made second-team All-American.”

Yes, the film’s hero George Bailey generously pays for his little brother Harry’s college tuition so that he can gallop across the gridiron while George stays home and runs the family business (as the board demands).1 But these two lines—and a moment where minor character Sam Wainwright tells Harry that his football coach is looking for a “great end”—are all we know about Harry’s illustrious football career. Hell, the film doesn’t even say what school he played for.

But I believe there’s much to discuss about Harry Bailey’s football career. And how it ended long before it should’ve.

Firstly, there’s the matter of his team. Columnist Neil Best wrote a piece for Newsday years ago where he points out that the film’s original script actually stated that Harry (and Sam) played for Cornell University, but the legal team at RKO Pictures advised the producers not to specify a college. It makes sense that Harry would’ve played for the Big Red; though Bedford Falls is a fictional town, it’s widely believed to have been based on Seneca Falls, a town in Upstate New York that’s only an hour away from Cornell’s campus in Ithaca.2 Also, consider that Cornell was quite good when Harry was growing up—in fact, from 1921 to 1923, the Big Red were a perfect 24-0, absolutely crushing most of their opponents and receiving retroactive national championship recognition many years later.3 Can’t you just see preteen Harry decked out in red, cheering his heart out from the bleachers?

Then there’s the matter of what position Harry played. Sam only says “end” when offering Harry a spot on the team. So he could’ve been a defensive end, or he could’ve been a tight end or a split end (or wide out) on the offensive side of the ball. But football was played a bit differently 100 years ago. Substitutions weren’t allowed for the most part until the 1940s, mostly because of World War II (seriously). Which means most players would be on the field all the time playing both offense and defense. So Harry would’ve likely been a two-way player—especially if he was good enough for national recognition.

Now, about Harry’s All-American senior season. It’s worth noting that the Big Red improved each year that he played. Harry graduated high school in 1928, and Cornell was pretty mediocre that fall, finishing with a disappointing 3–3-2 record. They righted the ship over the next two seasons, finishing 6-2 in both 1929 and 1930; the former team outscored their opponents 204-60, but the latter improved to a 273-63 scoring margin. And then (almost) everything clicked into place in 1931 when Harry was a senior. Not only did the Big Red finish 7-1, they only allowed 20 points all season—six of those points were scored by the Niagara Purple Eagles, and the other 14 were scored by Dartmouth when Cornell finally found themselves on the wrong side of a shutout.

After that scintillating season, Harry Bailey was, as we know, named a second-team All-American. And then his career was over. He married a girl named Ruth and went to work for her father at a glass factory in Buffalo.

That’s the real tragedy of It’s a Wonderful Life, if you ask me. If he’d been born a couple decades later, Harry would’ve had the chance to attain generational wealth through a lengthy professional career. Sure, the NFL existed in 1932 with a total of eight teams, but the NFL Draft wasn’t instituted until 1936, and even then most draftees turned down their contracts because the pay was so low. Perhaps Harry would’ve done the same had he been offered a deal. Or maybe he was eager to play on the professional level and the general managers simply weren’t keeping a watchful eye on Ivy League football.4 We’ll never know, unfortunately.

But I can tell you one thing about Harry Bailey’s fictional football career: It will always hit home for me on a personal level. That’s because my grandfather’s real college football tenure overlaps with his right down to the year.

Hugh Mooney was a backup center for the Alabama Crimson Tide from 1928 through 1931, just a couple years before Paul “Bear” Bryant suited up.5 He’s #23 in the top right corner of this 1931 team photo. He wasn’t an All-American talent, but he did have a similar brush with greatness.

His junior year, head coach Wallace Wade led the Tide to a sterling 9-0 record including seven shutouts en route to facing the Washington State Cougars in the Rose Bowl on New Year’s Day. But given that this was the Great Depression, even the University of Alabama couldn’t afford to send the whole team to Pasadena. So they had the backup players at every position flip a coin to see who got to travel with the team—and he lost. Alabama went on to crush the Cougars by a score of 24-0 (and claim a national championship), so he probably would’ve gotten a few snaps in. Alas.

Harry didn’t get to play in the NFL. Hugh didn’t get to play in the Rose Bowl. That’s the way the ball bounces. Thankfully, over the last century, America has come around and rightfully made college football its top priority, especially during these cold winter months. It’s a wonderful life indeed.6

It’s a Wonderful Life is now streaming on Amazon Prime and Hoopla, and it is available to rent elsewhere.

I realized how odd it was on a recent rewatch that Harry would have to pay for school despite being an All-American talent. But I discovered that athletic scholarships didn’t really become a thing until the mid-1930s. In fact, the NCAA didn’t allow student-athletes to receive scholarships for purely athletic reasons (with little regard to academic ability) until 1956.

Google Maps says it’s actually a 51-minute drive between the two cities today, but I rounded up because I didn’t feel like calculating average automobile speeds in the 1920s.

Cornell’s 1921 team received an invitation to play the also undefeated California Golden Bears in the 1922 Rose Bowl, but they declined it so that their players…could study for their exams. The Washington & Jefferson Presidents (coached by a man named Greasy Neale) played Cal in that Rose Bowl instead. The game ended in a 0-0 tie. College football used to be so pure.

You’d think Cornell would’ve been on the league’s radar given that three of the NFL’s eight teams were based in New York. Including one called the Staten Island Stapletons.

According to the internet, Alabama has never played Cornell in football, so he wouldn’t have squared off against Harry.

Unless you’re an Alabama fan in 2024. (Sorry, Granddaddy.)

https://youtu.be/_e7vvUShwYY?si=BbCrPYhGRK1bT-U5

Roll Tide