I don't remember most of my dreams. But the day David Lynch died, I woke up with a vivid recollection of a dream I’d just had.

I’d dreamed that I had a pet penguin named Chris. He was a foot and a half, maybe two feet tall. I think he might've been a king penguin, but not a very tall one. I'd taken Chris to work with me, at a clean but unremarkable office building, and everyone seemed to be fine with it. That is, until a mean lady decided to try and prove that Chris wasn't a real penguin. She put him under a device that looked like a cross between a paper cutter and a guillotine and let the blade fall, and it sliced him across his belly. There was no blood, but there was a small pile of gray and pink guts that sat next to him as he writhed in pain. I thought Chris was going to die at first, but then I realized that he wasn't dying, he just needed help. So I began calling local veterinarians to see if they could treat a penguin; I recall asking my mother if her local vet would take him.

And then I woke up. I decided that Chris eventually got stitched up and continued to live a happy penguin life in my dream world, and I went about my day. About five hours later, I heard the news that Lynch had passed away.

“My dream sounds a lot like Eraserhead” feels like a silly and pretentious thing to say, but I couldn’t shake the thought as soon as it hit me. Had the spirit of David Lynch visited me in the night as he was drifting toward the afterlife? Had I transcended consciousness and reached a higher plane of existence? Had I seen a future that I couldn’t yet understand?

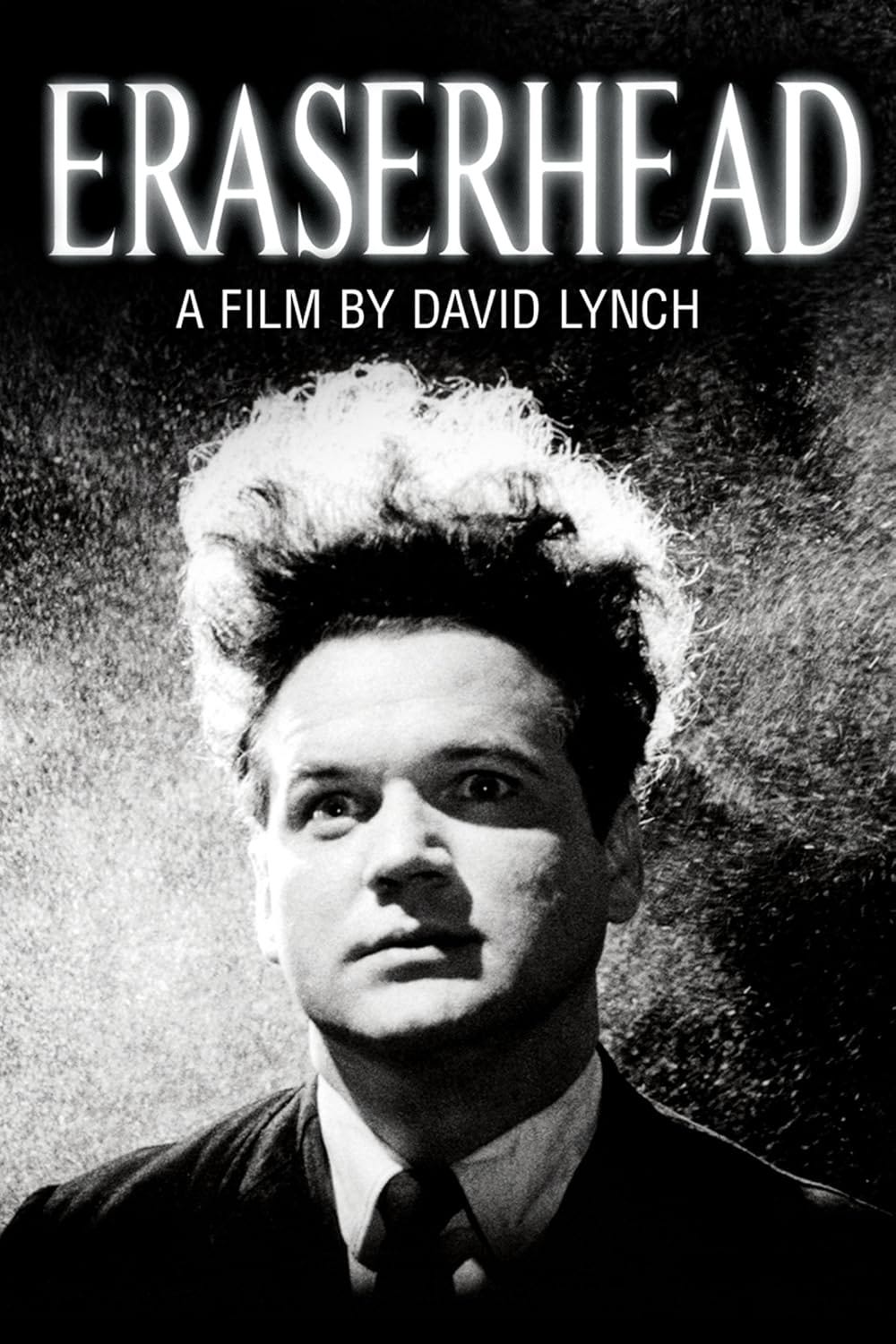

No, probably not. But it was nonetheless a small, strange gift to alleviate the sadness. A reminder that Eraserhead, my favorite of Lynch’s films, is his most dreamlike (or nightmarish).1 And according to him, it’s also his most spiritual.

I’m of course referring to one of the most well-known Lynch quotes that’s enjoyed a sustained life of mild virality in the digital age. “Believe it or not, Eraserhead is my most spiritual film,” he says, prompting the interviewer to ask him to “elaborate on that.” “No, I won’t,” Lynch responds bluntly. But if you’ve only seen the meme version of the quote, you’ve missed some context: Lynch laughing at his own reaction, the interviewer laughing with him, then Lynch adding that “No one sees it that way, or maybe somebody out there does, but it is.”

Last month, I spent a week in Florida rewriting an old screenplay, and I loaded up my Audible library with books that I thought would spark some creativity. One of those was Lynch’s Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity. (See? It’s right there in the title.) It didn’t exactly lead me to any great revelations about my task at hand, but it was an enjoyable (and brief) listen.2 In that book, he clarifies this point about Eraserhead a bit—and, in classic Lynch fashion, introduces another mystery to go along with it:

“Eraserhead is my most spiritual movie,” he states again. “No one understands when I say that, but it is. Eraserhead was growing in a certain way, and I didn’t know what it meant. I was looking for a key to unlock what these sequences were saying. Of course, I understood some of it; but I didn’t know the thing that just pulled it all together. And it was a struggle. So I got out my Bible and I started reading. And one day, I read a sentence. And I closed the Bible, because that was it; that was it. And then I saw the thing as a whole. And it fulfilled this vision for me, 100 percent. I don’t think I’ll ever say what that sentence was.”

To my knowledge, he never did reveal the scripture in question.3 But like Lynch’s best work, maybe its being a mystery makes this musing is all the more impactful. He was raised as a Presbyterian and he died as a transcendental meditator—he says in Catching the Big Fish, which was published in 2006, that he hasn’t missed his twice-daily meditations in 33 years, so one can only assume he reached the half-century mark before his health began to decline. So perhaps the answers to Eraserhead, to the spirituality found in his entire catalog, lie somewhere between those two poles.

But what does it mean for a film to be “spiritual” anyway? In the purest sense of the word, spirituality deals with things that exist beyond the physical world, beyond our physical bodies. Cinema, art in general, can be a spiritual experience, though it’s almost impossible to share the same experience with someone else in that sense.

Could it be that dreams are the closest thing we humans have to a shared spirituality? We don’t have the same dreams, but we all dream, even if rarely. Lynch said that he didn’t remember much from his dreams, so he didn’t get his ideas from them.4 But he “love[d] daydreaming and dream logic and the way dreams go,” and that’s pretty clear if you’ve seen even just a few of his films. Perhaps being “spiritual” also implies an aspiration to be comfortable with things that cannot be explained, and Lynch does everything but explain his themes (or even his plots).

It would be too easy to say that “spiritual” and “dreamlike” mean the same thing, especially in regards to a David Lynch picture. But I love the way he created works of art that opened up to countless interpretations. Much like dreams. Much like spirituality, perhaps.

Maybe my dream wasn’t a premonition linking me psychically to one of America’s greatest filmmakers. But I’ll leave you with this, reader. When I got home from the office last night, before I cooked dinner and watched David Lynch: The Art Life and wrote this newsletter, I opened Audible and fired up Catching the Big Fish once again to see if Lynch’s writing might inspire mine in some way knowing that I’d be leaning heavily on my stream of consciousness for this one.5

Can you guess the first word he said? It was the beginning of the opening credits. It was the name of the audiobook publisher. It was “penguin.”

Eraserhead is now streaming on Max and the Criterion Channel, and it is available to rent elsewhere.

I actually dozed off a little bit last time I saw Eraserhead, exactly 11 months ago. In my defense, I went to a midnight screening at the Sidewalk Cinema with my cousins, so we were sleepy. But let me tell you: It only added to the vibe.

Another book I listened to that I would highly recommend: Jeff Tweedy’s How to Write One Song, which is also pretty short (about four hours) and has lots of great talking points for artists of all kinds, not just musicians. (Tweedy sings a bit too.)

Stephen Aspeling over at Spling Movies wrote a fun exercise that explores some verses that seem like plausible culprits.

He was just like me, for real.

I could not burden my editor John with reading this draft, since I finished just after 11:00 and he has a newborn baby. So I hope it makes sense!

When Mel Brooks, producer of "The Elephant Man", hired Lynch to direct that film, he told him that "You're a crazy man". That assessment was based on his viewing of this film, which firmly established the Lynch directorial canon as a "crazy" one rivalling the similar one of Brooks himself. Crazy people can spot each other a mile away.

Cheers to Chris.