Today’s issue of Dust On The VCR is a subscriber request! This film is brought to you by my longtime film friend Trey Jordan, who just watched it and was unsurprisingly blown away. Trey isn’t just a filmmaker—he’s a film scholar. And conveniently for you and me, reader, he just launched a new project called First Matter Films, which is a combination of a Substack newsletter where he’s been breaking down great films in insightful ways and a YouTube channel where he’s been interviewing professional screenwriters about their careers. (I particularly enjoyed his newsletter about In The Heat of the Night and his interview with Thompson Evans.) Maybe he’ll even write about Cure soon so that our newsletters can team up and take over Substack’s algorithm. Anyway. Wanna request a film for a future issue of Dust On The VCR? Subscribe to the paid version!

No Country For Old Men was a formative moment for me in my film journey. Not just because it’s a masterpiece—you don’t need me to tell you that—but because it reached such a wide audience that it elicited plenty of polarized reactions.

I loved it as soon as I saw it.1 And I loved the ambiguity of the ending in particular. It felt literary to me, like a great novel that leaves you with a punch to the face or a shake of the shoulders on the last page. But many of my friends, family, and acquaintances were quite frustrated by the ending, so much so that it undid the good will they had toward the film through most of the runtime.

Those people wanted answers, plain and simple. To them, the ending wasn’t a magnificent final chapter—it was as if the manuscript wasn’t even finished. They needed to know what happened to Anton Chigurh. They needed to know what Sheriff Ed Tom’s dream meant.2 They needed closure, and while I didn’t agree with their assessments, I could understand their desire after a journey like that.

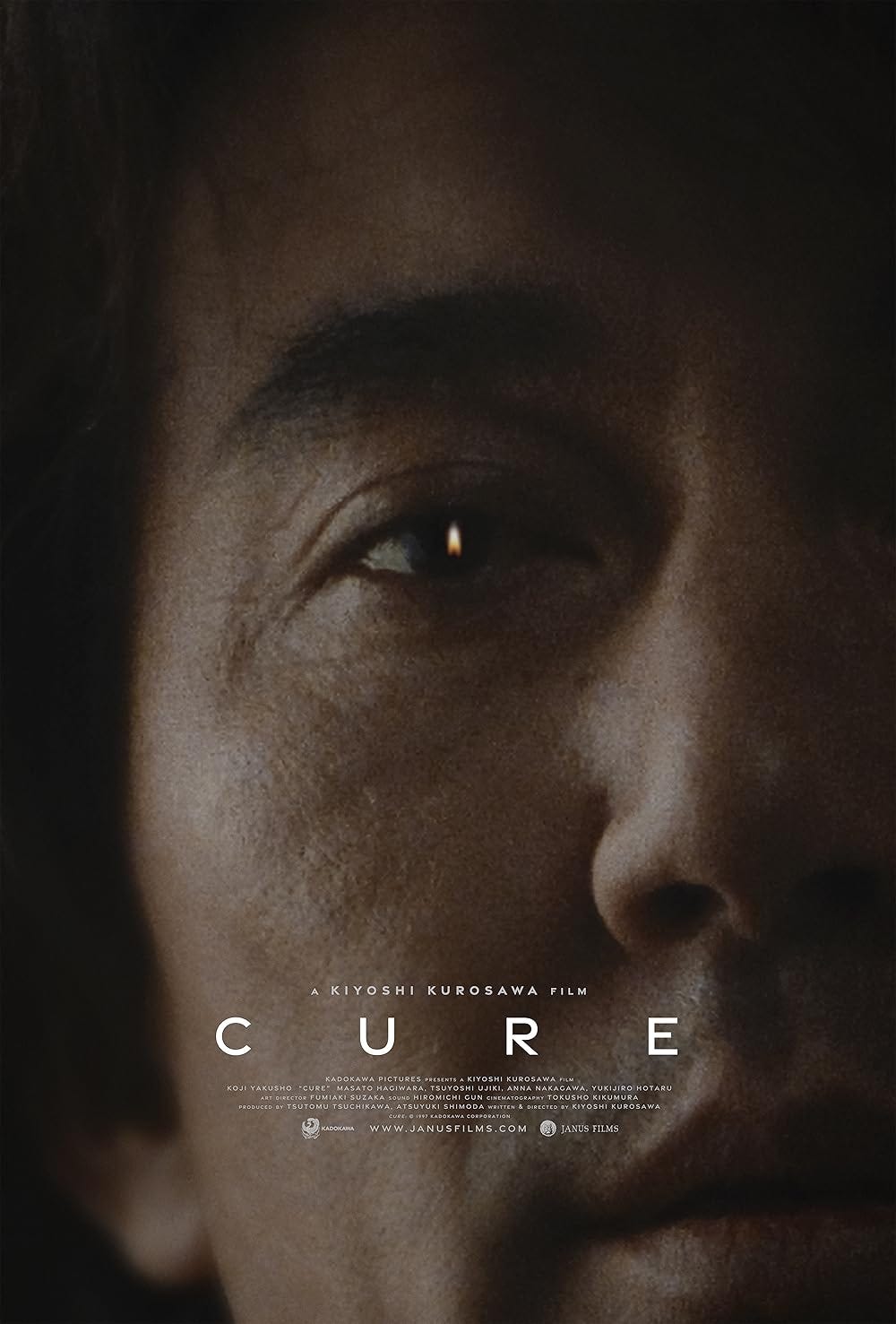

Sometimes, a film’s secret weapon is its willingness to leave viewers with unanswered questions. It can be a hard trick to pull off, and a story can completely fall apart if an ambiguous ending isn’t executed well. Thankfully, a decade before the Coen Brothers’ brilliant adaptation, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure gave them (and us) a modern blueprint for such a technique.

Cure begins as many crime thrillers do: with a series of grisly murders. The Tokyo Metropolitan Police (not to be confused with the Tokyo Gore Police) are investigating a handful of seemingly unmotivated killings that all involve an X being carved into the victims’ necks after their death. The killers don’t have any criminal histories, nor do they have any connections to each other. Needless to say, the cops are stumped.

As the narrative unfolds, the film lets the viewer be stumped as well. We see a man named Kunihiko Mamiya—who doesn’t seem to remember anything about himself—calmly interact with the various killers before they commit their murders, all without so much as raising his voice.3 He simply shows up, asks these people questions about themselves, and leaves just before they go homicidal.

The story raises numerous questions ranging from “What does it all mean?” to “What the hell is actually going on right now?” And Cure does provide some clues rather than leaving the audience totally in the dark. But as the drama unfolds, it becomes clear that the questions themselves are more important than the answers.

This approach has delighted thousands of cinephiles since the film’s release.4 And I’m sure it’s frustrated many others who were looking for something more accessible. One of the brilliant things about Cure is that it gives both sets of viewers a proxy character to relate to.

Kenichi Takabe, the protagonist of the film, appears to be one of Tokyo’s top detectives. He’s the kind of workhorse policeman who doesn’t really know how to maintain a personal life (all at the expense of his wife Fumie). His relentless investigation drives the narrative forward in a propulsive way as we see him grow increasingly frustrated with the dead ends he comes to—even once he has Mamiya in a holding cell.

But Detective Takabe isn’t flanked by a scrappy young cop with something to prove. Nor is he being pressured and bossed around by a grizzled old veteran. Instead, we see him consistently seeking the wisdom of Dr. Shin Sakuma, a forensic psychologist at one of the local hospitals. He is the yin to Takabe’s yang every step of the way, dropping knowledge at opportune times and even cautioning Takabe not to bite off more than he can chew with Mamiya—a smart bit of advice from the smartest character in the saga.

It’s the perfect pairing for a psychological thriller. One provides the psychology, the other provides the thrills. And ultimately, one feels comfortable lingering with the questions while the other desperately seeks the answers. It’s a tricky balancing act to pull off, which makes Cure a masterclass in dramatic ambiguity—and one that’s been highly influential over the last three decades.5

Cure is now streaming on the Criterion Channel, and it is available for rent elsewhere.

A very brave and unique take, I agree.

If I’m being honest, I still don’t really know what Ed Tom’s dream means beyond guesses at the general symbolism. But I love that the dream doesn’t yield an easy interpretation. And I love that the film ends with a monologue describing a dream. “And then I woke up.”

In an incredible touch, this harbinger of mayhem is mostly seen wearing a remarkable outfit: stylish boots, well-fitting khakis, and an incredible cable-knit sweater, all complementing each other well in muted, earthy tones. Unfortunately, I think he might be my fall fashion inspiration.

It’s currently ranked 189th in the Letterboxd Top 250, between The Iron Giant and 2001: A Space Odyssey.

As my comrade Garrison Ryfun reminded me, Bong Joon Ho credits Cure as a direct inspiration on his Memories of Murder. Which paved the way for David Fincher’s Zodiac, which paved the way for Denis Villeneuve’s Prisoners, etc.

I have some ideas on Cure and No Country. These will officially be the subject matter of my next writing.

Thanks for sharing this Jeremy! My VCR is humming like a choir now!