28 Days Later (2002) Reminds Us That Sometimes Movies Should Look Like Crap

Reader, I finally got around to seeing 28 Years Later this past weekend. I really liked it for the most part, even though Danny Boyle and his crew made some…interesting decisions. But this new installment also provided a great excuse to revisit the earlier films, which I try to do whenever a long-dormant franchise gets dusted off.

I hadn’t seen 28 Days Later in many years—possibly since it hit theaters.1 I remembered loving it at the time, and I was excited for a long-overdue revisit. But when I pressed play, I was quickly reminded of one thing in particular: “Oh yeah, this movie looks like crap, doesn’t it.”

Of course, I am far from the first person to point this out. I’m sure film critics and proto-bloggers pointed it out in 2002 as well. But it was a fascinating thing to behold in 2025 when so many classic films are being remastered and upgraded.2 For a moment, I wondered if I’d accidentally rented the standard definition version on Amazon.3

I am also not the first person to point out that the film’s fuzzy, dingy visuals actually enhance the experience in an interesting way. I mean, it’s a zombie movie, innit? The world of 28 Days Later is an ugly one, what with rage-stricken hordes chasing scattered survivors around and uninfected human beings acting even more monstrously and the remnants of a societal collapse all around them.

So it makes sense that the presentation of such a world would be similarly ugly, despite the fact that the cinematography is all very well composed. It looks like footage from a news reel or a home movie or a primitive camera phone. It looks like something we weren’t supposed to see.

My buddy Franco sent me a link to a pretty great video essay by Archer Green on this very topic that says all of this better than I could.4 But it also points out that this intention by Boyle and his cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle is only part of the reason why they shot it this way.

To summarize, there was also a practical advantage to shooting with digital cameras in low definition. Boyle’s team captured some incredible footage of deserted London streets for the first act of the film, and because they could only get these busy thoroughfares blocked off for a few minutes at a time, they had to shoot quickly and with multiple cameras. So digital cameras were their only option. And then they kept shooting fast and loose in 480p so that (almost) the rest of the film would match those scenes.

It’s useful context that adds a level of appreciation for the film. At least for people like me. But there are lots of people who aren’t like me. So why is the visual palette such a detractor for many modern viewers?

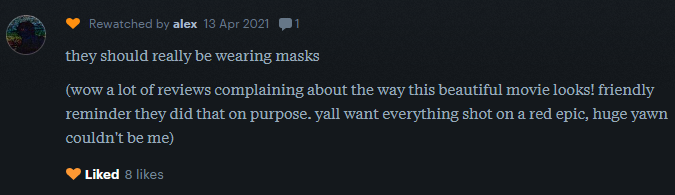

As I was combing through Letterboxd reviews of 28 Days Later, I stumbled upon a review by Alex Jacobs, editor of In A Violent Nature and one of the editors on V/H/S/99 and V/H/S/85, whom I met a couple years ago at our mutual friend’s film festival.5 And he summed it up in a way that really struck a chord with me:

For those of you who don’t work or play with cameras, Red is a digital camera company that became somewhat of an industry standard over the past couple decades because of how closely it can replicate the quality of 35mm film. The Red Epic was released in 2010 and was used to shoot lots of big-budget fare like Prometheus, The Hobbit, Flight, The Amazing Spider-Man, Lone Survivor, The Great Gatsby, and a handful of Marvel movies.6

That collection of titles is a telling one, I think. Because technically they all look flawless. But oftentimes, when your product appears to be flawless, it’s not very interesting or memorable either.

Perhaps it’s not a coincidence, then, that the first Red cameras (the aptly named Red One) were shipped out the same year that Netflix pivoted to streaming (2007). And that Netflix started releasing their first streaming originals right around the time those Red Epic feature films were hitting theaters.

Of course, people much smarter than me have taken deeper dives into the fact that Netflix films and shows all kinda look the same (and very much by design). But I’m less concerned with Netflix’s reasoning for that decision as a producer than I am with the effect it’s had on us as consumers. Sure, there’s some good stuff on Netflix, and even the bad stuff generally looks fine. (Technically.) But I fear that this monotony is wrecking our sensibilities. I fear that we’ve been force-fed a standard of what looks “good” for so long that we’ve begun to equate anything that looks different with looking “bad.”

And technically, 28 Days Later does look “bad.” But it looks so, so different and so unique. Even setting aside the fact that practicality was the main driver of Boyle’s decision, I think it’s hard to argue that it’s a well-crafted film. Green’s essay spells it out quite nicely: “Looking great is a bonus. [Cinematography] has to inform, reflect, and build upon the story being told. It has to match the vibe of the overall movie.”

Sometimes looking good is all the cinematography does. Sometimes it’s all bonus and no salary. I’ll take the informing, reflecting, and building every time.

28 Days Later is now streaming on AMC+ and Pluto TV, and it is available for rent elsewhere.

This was one of the movies I snuck into when I was a delinquent teenager. The experience wasn’t as eventful as the time I snuck into 8 Mile, but there was an employee waiting for us at the theater entrance. Turns out he was checking IDs, not tickets. (I had just turned 17 a month earlier, thankfully.)

Is it too soon to call 28 Days Later a “classic?” I don’t think so, but if you do, might I remind you that the term “classic rock” was applied to bands that had only been around for a decade when I was growing up.

Yes, I paid $3.99 to rent it when I could’ve watched it for free with commercials on Pluto TV, even though the resolution wasn’t any better and I wound up pausing it several times. I contain multitudes.

Franco is also a paid subscriber of this newsletter, so if you’d like to upgrade your subscription (or you are already in the paid tier), you can also send me as many video essays as you would like. I promise to occasionally watch them when they serve my schedule and my needs.

That mutual friend is Anton Jackson, and his film festival is the Montgomery Film Festival. And wouldn’t you know it, they just dropped this year’s lineup! And obviously the lineup is great as usual! I love this festival. Tell all your friends.

Gone Girl and The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo were also shot with Red cameras, but David Fincher is innocent in this house.

When I got my copy of the Blade Runner remastered Blu (after having seen it countless times on VHS) I was a little freaked out. No! This movie is not supposed to be this clear, bright and detailed.

I put this on my Top Ten list when everyone was doing the NYT thing. :) I love this movie. I love the way it works. I am so tired of everything being glossy, buffed, shiny, fake. One of my all time favorites, and I feel similarly about 28 Years Later... how refreshing to not have to look at everything smoothed to shit!