The Misfits (1961) is a Swan Song for Old Hollywood and the Wild West

Note: Today’s newsletter contains minor spoilers for The Misfits, a largely plotless film that I don’t believe would be ruined by prior knowledge of some events. But if you’re intrigued by the first half of today’s piece and you want to maintain a clean viewing, I’d suggest watching the film before reading the second half!

If there’s one thing I didn’t anticipate of our current decade (are we just calling it “the 20s” again?), it’s that Adam McKay would become a more interesting podcaster than filmmaker.*

If you’re a basketball fan, I highly recommend his 2021 podcast series Death At The Wing, where he delves into the tragic passings of an unusually high number of rising NBA prospects and the social and political ramifications of those events. But today’s newsletter was inspired by McKay’s new follow-up podcast series Death On The Lot, which again breaks down a concentrated grouping of fatal occurrences but this time focuses on the end of Hollywood’s Golden Age.

He spends the first few minutes of the first episode talking up The Misfits, a John Huston neo-Western (or anti-Western?) that I’d never seen before this month or even heard of before McKay’s recommendation. He opens with this film for a particular reason: More than perhaps any other film, The Misfits accidentally foretold the end of this particular era.

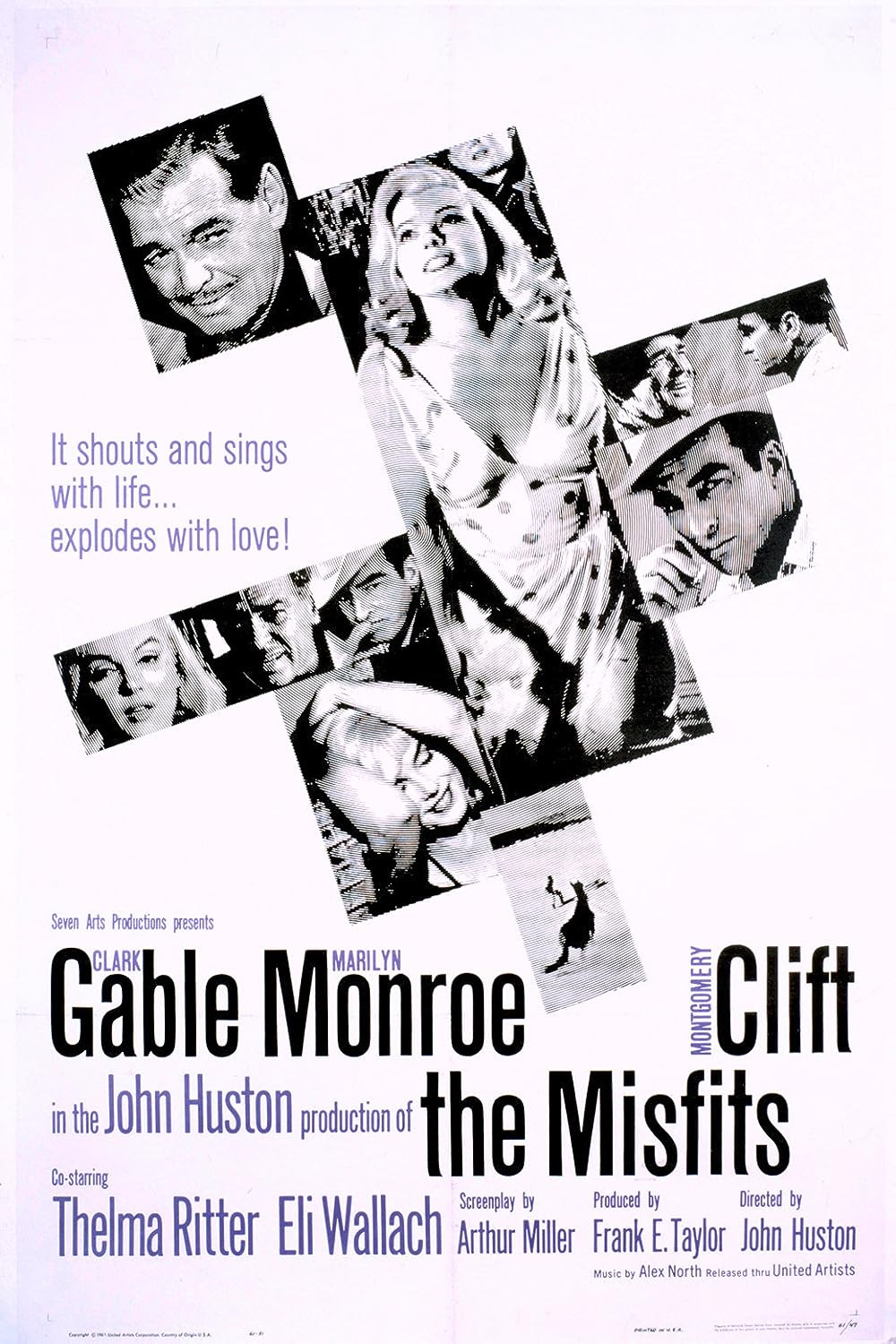

The Misfits stars a trio of Golden Age screen legends in Montgomery Clift, Marilyn Monroe, and Clark Gable.** But just five years after it was released, Clift would die from a heart attack likely brought on by years of substance abuse at age 45. And just one year after The Misfits hit theaters, Monroe would die in a probable suicide by way of a pill overdose at age 36. As for Gable, he would also die of a heart attack at age 59—before the film was even out. (It would be the last screen appearance for the latter two.)***

Given this haunting distinction—and the fact that it’s a great film—I’m kinda surprised that The Misfits isn’t more well known and widely celebrated. But there’s a complementary thread to it that McKay doesn’t get into much: Though it came to represent the decline of Hollywood’s Golden Age, the film itself is largely about the demise of a different era: the American West.

Monroe’s character (Roslyn) is the crux and the catalyst of the film, finding herself in present-day Reno to secure a divorce from her husband. And then wouldn’t you know it, in a true Old Hollywood move for a female character, she doesn’t even last a day before meeting her next romantic interest: Gaylord, played by Gable.****

The symbolism isn’t subtle as Roslyn and Gable quickly become a pair. She’s an idealistic, modern woman who loves animals so much she’s willing to let rabbits ruin her garden. He’s an aging, underemployed cowboy who’s clinging onto a dying way of life, desperate for any gig that’ll allow him to stave off a day job. “Anything’s better than wages,” he reminds us often.

Things get more interesting (and the symbolism even richer) as they meet Clift’s character, Perce, a local wrangler itching to find his next rodeo. Gaylord pays his entry fee, and Perce winds up getting thrown by a horse so badly that Roslyn begs him to go to a hospital. Instead, he gets on a bull, gets bucked off again, and gets knocked unconscious upon landing. Perce is much younger than Gaylord, but he’s no less obsessed with the ancient rules of American masculinity.

Now that he owes Gaylord for his rodeo ticket, Perce agrees to help him with his latest prospect: rounding up a herd of wild mustangs Gaylord recently spotted so that they can sell them. It all leads to a third-act climax that might as well be the nail in the Old West’s coffin as each character finds a fitting end to their narrative arc.

I can’t recall ever seeing such an extratextual confluence in one film like what The Misfits ultimately came to be. Huston and Miller were commenting on and pushing past the Westerns of the 40s and 50s, sometimes shouting the themes rather loudly. But who could’ve known that the film would become a sort of cultural double helix just a handful of years later, accidentally digging two graves like Confucius’ vengeful protagonist?

In a just world, The Misfits would be one of the most celebrated films of the 60s. And perhaps it’s just one boutique blu-ray away from a minor revival. Until then, it makes for a hell of a podcast hook.

*Despite largely agreeing with its message, I wasn’t too fond of Don’t Look Up. Maybe he’ll win me back with his upcoming serial killer comedy.

**The fourth star (or top supporting actor) would be Thelma Ritter, whom I wrote about a couple years ago. She’s absolutely marvelous in her limited scenes.

***Monroe did shoot one more feature—George Cukor’s Something’s Got To Give—but the film was scrapped by 20th Century Fox before it was finished. (Monroe was actually fired from the film before she passed.)

****I’m fascinated by Monroe’s character in this film. At times it feels paper thin, but there are layers that come and go in interesting ways. Most intriguing of all is the notion that famed playwright Arthur Miller—her husband at the time—was the sole screenwriter here.

The Misfits is now streaming on Kanopy, Pluto TV, Freevee, and the Criterion Channel, and it is available for rent elsewhere.