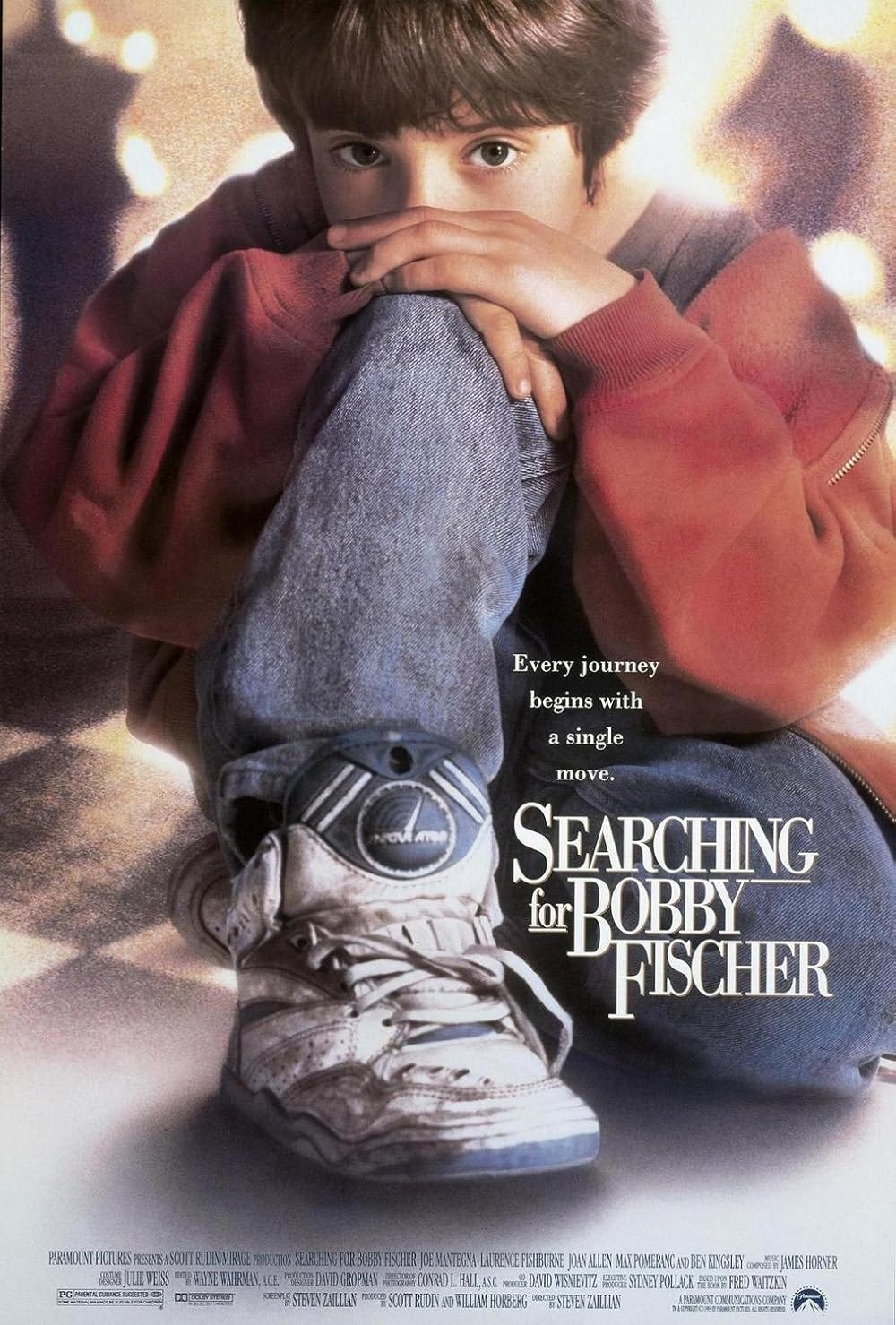

The "Villain" Kid in Searching for Bobby Fischer (1993) Does the Right Thing

Today’s issue of Dust On The VCR is a subscriber request! This comfort classic of the mid-90s was selected by my dear friend Matt White, who has actually been featured in this newsletter before (when I introduced his eldest son to Godzilla by showing him All Monsters Attack.) Matt and I are college buddies from way back, and I’m thankful that he’s one of my friends from that era that’s stayed in touch regularly all this time. We’ve even had plenty of movie nights with friends of ours—everything from the Michael Hutchence documentary to The Room. Matt chose today’s film because it’s a good example of how we watch some movies differently as we get older and have families, and I was happy to do a demented deep dive into the film’s climax. (Which means spoilers abound, if you hadn’t already assumed.) Anyway. Want to request a film for a future issue? Subscribe to the paid version!

Searching for Bobby Fischer isn’t very shy about its theme. I think you could sum it up: “It’s more important to do your best than to be the best.” But it’s the kind of sports movie that has its cake and eats it too.*

The story focuses on Josh Waitzkin, a seven-year-old kid who learns how to play chess and soon discovers that he’s a prodigy—or “the next Bobby Fischer” as observers of the Washington Square Park chess hustlers like to say whenever they encounter a skilled young player. But after Josh’s father becomes obsessed with his son’s talent, enrolling him with a strict mentor and entering him in every chess tournament on the East Coast, Josh loses his love of the game as it becomes all work and no play. The message here is that it’s more important to have a kind heart than a competitive spirit.

But it is a sports movie after all. So a “villain” is presented in the second act in the form of Jonathan Poe, another wunderkind who might just have what it takes to steal Josh’s crown. Though he’s rightfully seen as a product of his upbringing (his father takes chess too seriously and is generally pretty unkind), Jonathan is painted as the cautionary tale of who Josh could become if he cares too much about winning. His presence reinforces the message: His competitive spirit has overtaken his potentially kind heart.

Once Josh and his father reconcile and his love for chess returns, the film naturally builds up to a showdown with Jonathan at the National Chess Championship. The result of the final match is unsurprising, but an interesting thing does happen along the way—one that I found to be rather unfair to Jonathan.**

I actually thought for a minute that the film might end with Josh losing the final match, but that would’ve mixed the messages. Sure, it would’ve reinforced that there’s more to life than chess and Josh would’ve probably shrugged, smiled, and said “good game” (which he ultimately does), but it would’ve also allowed an inordinately competitive spirit to triumph over and thus exploit a kind heart. And we can’t have that in an inspirational sports movie, right?

So writer/director Steven Zaillian throws us a curveball: Josh, seeing a sure victory several moves away, holds out his hand and offers Jonathan a draw.

This really hammers the theme home. Josh knows he has Jonathan beat, but his heart is so kind that he cares more about his opponent’s feelings than his own victory. And that’s all well and good, of course. But Jonathan’s reaction—“Draw? You’ve got to be kidding.”—followed by his swift defeat implies that he makes the wrong decision. And I’m here to tell you that he doesn’t.

Since the film reiterates the theme over and over, I’ll state it a second time: “It’s more important to do your best than to be the best.” With that in mind, would taking a draw have been Jonathan “doing his best?” Would it have been any player’s best?*** Jonathan refuses to give up, and he tries his hardest to beat his opponent. He even takes it relatively in stride, showing no anger or bitterness toward Josh (even though he doesn’t return Josh’s “good game” remark).

Sure, he’s a little boastful during the match. And yes, he could be more gracious when ultimately accepting defeat. But he’s also seven years old. Most kids his age would’ve cried their eyes out, and more than a few of them would’ve swiped those chess pieces to the floor during a tantrum.

Even though his dad’s not exactly a good role model, Jonathan still worked hard, played his best, and never gave up—even when his opponent framed it as a wise choice. If he was my son, I’d be proud of him. (And then hopefully I’d be a little bit nicer to him.)

*I appreciate the meaning of this idiom, but I’ve always kinda hated it. Why are y’all out here just staring at cakes? Don’t cakes exist to be eaten? Thanks for coming to my TED Talk.

**One other small but interesting choice for the final match: Josh is wearing a black shirt and Jonathan is wearing a white shirt. Their wardrobes do coordinate with their chess pieces, but come on, didn’t Steven Zaillian grow up watching Westerns? Weird time to be subversive, sir.

***As Jay-Z once said, moral victories is for minor league coaches.

Searching for Bobby Fischer is now streaming on Hoopla and Paramount+, and it is available to rent elsewhere.