Fargo was one of the first Coen Brothers films I ever saw, back in high school. I’ll never forget that opening title card and the haunting rationale it included:

“This is a true story. The events depicted in this film took place in Minnesota in 1987. At the request of the survivors, the names have been changed. Out of respect for the dead, the rest has been told exactly as it occurred.”

What a way to kick off a crime drama! It’s so good I’m not even mad that it’s completely bogus. I can’t remember how many years later it was that I found out that Fargo is not, in fact, based on a true story, though maybe this was understood by audiences at the time.* But I realized pretty early on that the Coen Brothers are geniuses, so any feeling of being deceived by this disclaimer was slight and short-lived.

Geniuses though they may be, the Coens weren’t the first filmmakers to use this trick.

It might not be the earliest example of false advertising on film, but let’s jump back almost a quarter century to The Legend Of Boggy Creek, an independent film about a Bigfoot-esque creature called the Fouke monster that was made in the Texarkana area. This spooky docudrama, a precursor of sorts to the found footage subgenre, claimed to be a true story as well. But…it’s Bigfoot, you know? To believe that The Legend Of Boggy Creek was real, you had to already believe in Sasquatch. I’m sure most viewers were skeptical, but even so, the film was a big ol’ hit, grossing somewhere between $20-25 million worldwide against a $160,000 budget.**

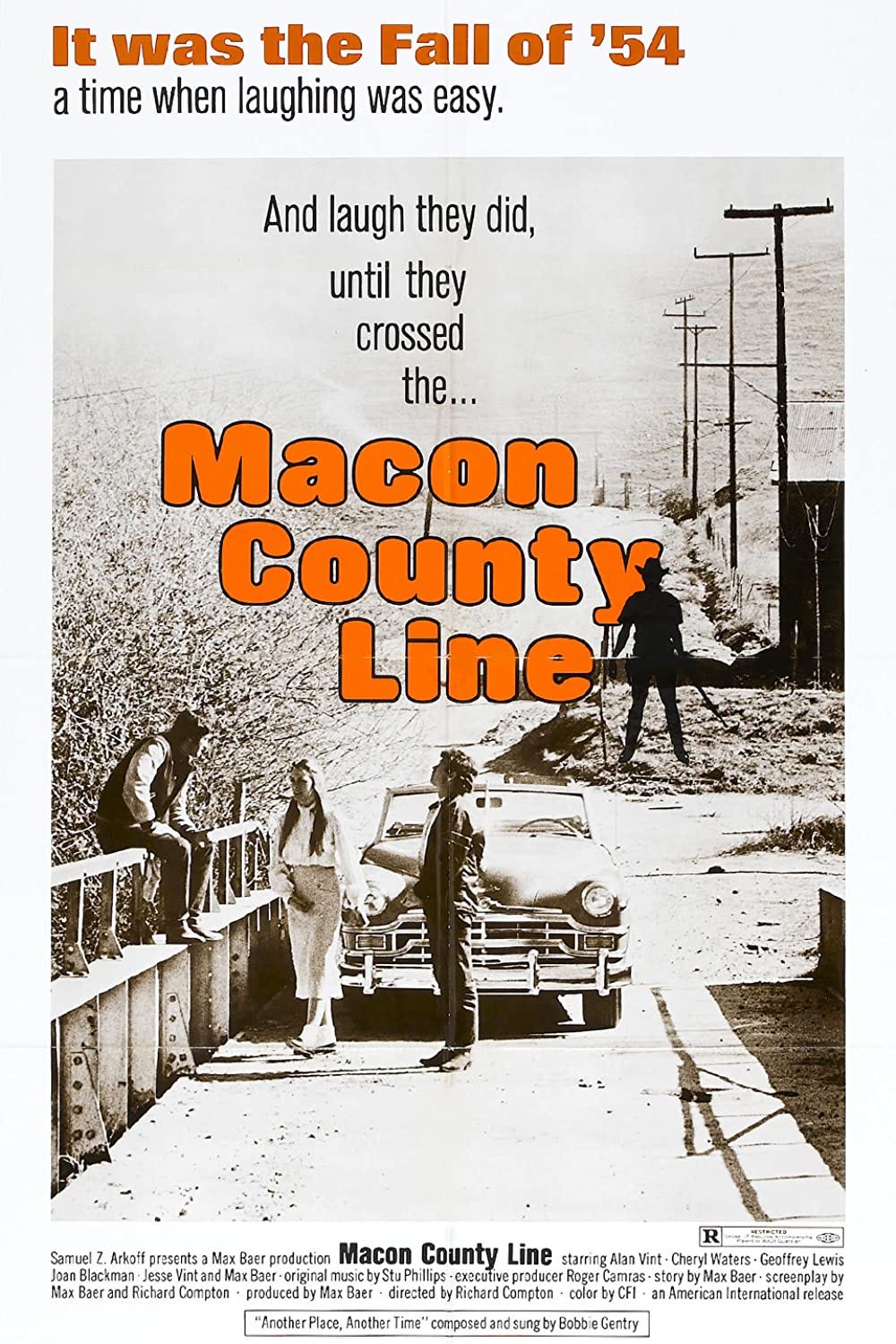

The Legend Of Boggy Creek greased the tracks for Macon County Line, another hicksploitation film that came along just a couple years later and used a similar marketing stunt—but in a different way.

Macon County Line was conceived by Max Baer Jr., known mostly for his role as Jethro Clampett on The Beverly Hillbillies. Baer thought he had more to offer the world of cinema, so he wrote a script, recruited director Richard Compton, and raised a modest sum of money to shoot the film in Sacramento and make it look like the South.

And it was also a big ol’ hit! The internet has conflicting numbers for this one too, but it appears that Baer and company spent no more than $225,000 on the film, and perhaps closer to half that amount. It set the box office on fire—particularly at drive-in theaters and in Southern cities—to an estimated tune of $30 million worldwide.

But none of it would’ve happened if they hadn’t lied to their audiences.

The film follows two brothers, Chris and Wayne, on a road trip through the South before they join the Air Force. As luck would have it, their car happens to break down…in front of the local sheriff’s house…right before a brutal crime is committed by two other men on the property. According to Compton, after the first test screening, audiences were largely questioning the nature of the plot, saying it was “too coincidental” to be believed.*** But this was a low-budget production, folks; they couldn’t just rewrite and reshoot crucial scenes to make them less coincidental.

So Baer came up with a rascally idea: “What about if we say it’s a true story, and only the names have been changed to protect the people that are still living?”**** So that’s what they did, simply adding that crucial text over the opening scene: “This story is true. Only the names and places have been changed.”

As Compton said years later, and as those dollar amounts confirmed, it was a smart move: “The audiences, once we put that little disclaimer at the head of it, it changed everybody’s attitude about the picture. By the time we screened it the second and third time, we knew that there was gonna be a big audience for this picture.”*****

Funnily enough, just two months later, Macon County Line was sharing screens with another insanely profitable Southern genre film that was falsely advertised as a true story: The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, which may or may not have actually been more profitable than Macon County Line, depending on which corner of the internet you ask. (Maybe I’ll hire a fact-checker next time.)

*Only three years later, audiences were in a frenzy over whether The Blair Witch Project was real or not, so I’m guessing that casual theatergoers didn’t just assume the Coens were making it all up.

**I couldn’t find a reliable source that confirmed it, but my go-to hicksploitation expert Joe Bob Briggs claims that The Legend Of Boggy Creek was one of the 10 highest-grossing films of 1972. Also, Wikipedia adds this: “Pierce's daughter…claims to have autobiographical notes made by her father indicating that the film ultimately made $25 million…but this cannot be verified.”

***Yes, I’m the guy who bought the Shout Factory blu-ray of Macon County Line and watched the making-of featurette. You’re welcome.

****It’s unclear if this idea was actually Baer’s, but he sure seems to take credit for it.

*****Macon County Line was such a hit that it spawned a much more tame sequel just one year later: Return To Macon County, which did not claim to be based on a true story. Also, nobody even utters the words “Macon County” (all you see is road signs in brief driving scenes that were surely pick-ups). But it does star a young Don Johnson and a young Nick Nolte, and the lead female character (Robin Mattson) says at one point that she was “Miss Birmingham Tool Supply in ‘55,” which has to count for something. Pretty good tagline in the trailer too: “To cross the Macon County Line once is wild. To cross it twice is insane.”

Macon County Line is now streaming on Peacock, Tubi, Pluto TV, and Freevee, and it is available to rent elsewhere.

Max Baer, Jr. played Jethro Clampett. Jed was played by Buddy Ebsen.