Happy January, reader! This month, I’m doing a new series that was inspired by creative laziness. You see, I’m teaching a four-week film class at Birmingham-Southern College, and since I’ll be watching films with my students anyway, I’ll be writing about some of those films here in the newsletter. Neat, right? Anyway, we reviewed the early 20th Century this week, which included Cat People, The Day The Earth Stood Still (which I covered a few months ago), and today’s film, Freaks, the oldest film we’re covering. Hope you enjoy this peek inside the classroom!

I think it’s only right that we start the new year with a bit of kindness, don’t you?

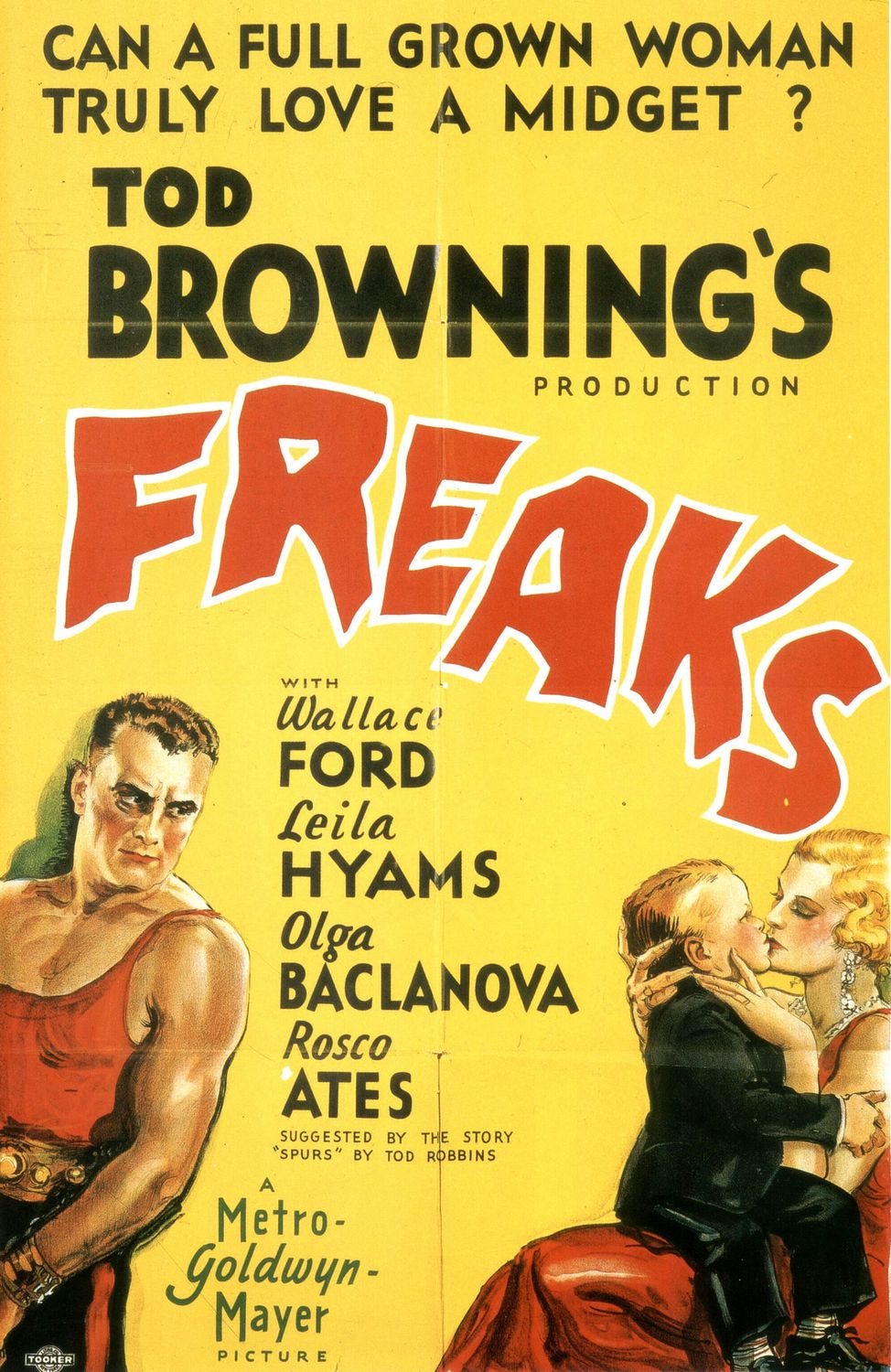

You may be wondering how kind a film called Freaks could be. And that’s fair. On the surface, it’s a rather exploitative title. And if you stick to that surface, you might think that a horror film about traveling circus performers—played by actors with real disabilities—would be rather icky in its treatment of the titular “freaks.”

Unfortunately, audiences in the 1930s mostly dwelled on that surface level too. Director Tod Browning had curried favor with audiences and critics alike just one year earlier with Dracula, one of the first horror films of the sound era. But Freaks yielded bad vibes from the jump.

The public backlash began with the test screenings. Here’s a quote from art director Merrill Pye: “Halfway through the preview, a lot of people got up and ran out. They didn’t walk out. They ran out.” (One woman even sued MGM, claiming the film had caused her to have a miscarriage.) It’s truly wild to imagine audience members running out of a test screening, but it’s devastating to know that they were running from the images of disabled actors playing a version of themselves.

The private backlash, however, was happening even as the film was being shot. Some of the cast and crew were reportedly disgusted by the disabled performers, so much so that they were given separate living quarters, and even a separate cafeteria for their meals.* It was a different time, of course, but it’s pretty shocking to think about.

Naturally, after the disastrous test screenings, the studio executives at MGM scrambled to salvage the film, which they did (in their eyes, at least) by cutting a third of the original 90-minute film and dropping in some alternate footage to get the new cut up to 64 minutes.** This of course did not sit well with Browning, who spent years working as a circus performer himself.*** The film went on to be a critical failure and a box-office bomb anyway, and it was the only MGM film to be pulled from theaters before completing its domestic engagements.

One of the most curious things about this whole debacle is a tagline that MGM deployed to counteract claims that the film is exploitative: “What about abnormal people? They have their lives, too!” It’s a tagline that’s representative of the film’s sympathetic lens too; in fact, the majority of the film merely captures the titular characters in their daily lives outside of the big top, laughing and drinking and smoking and even romancing. So while the studio did butcher the original cut of the film, they may have come around to see things Browning’s way, taking an empathetic stance against the backlash.****

Thankfully, a more earnest and widespread empathetic approach would come decades later through festival screenings, critical reappraisal, even an addition to the U.S. National Film Registry. Though there are arguable some exploitative elements to the film (and the production in particular), we can see nearly a century later that Browning—along with Tod Robbins, author of the short story that loosely inspired the film—was largely ahead of his time.*****

I think that’s the lesson here: If you want to be perceived as forward-thinking, err on the side of kindness. Browning saw a story to be told with Freaks, but his casting of disabled actors shows that he not only wanted to give them such an opportunity but he wanted to portray them in a more positive light than they were used to—a positive light that audiences at the time simply weren’t ready for.

But now we, as viewers, are more ready than ever, aren’t we? Even over the last decade or two, our vocabularies have changed, our attitudes have changed, and our natural inclination toward empathy has only increased. And our stories have followed suit accordingly, especially in film, a medium that Roger Ebert once famously said is “like a machine that generates empathy.” I think Browning would be proud. (And I bet Ebert liked Freaks.)

*Not everyone on set despised the disabled performers, though. Olga Baclanova, one of the able-bodied leads, said that she could hardly look at her costars at first, but after cameras began rolling, she “like[d] them all so much.” Hey, it’s progress.

**The original version sadly no longer exists. To our knowledge, at least. I will continue holding out hope that an intern stumbles upon an intact reel or a case of scrap footage in a vault somewhere.

***This man was crazy, folks. He ran away and joined the circus when he was just 16, and he earned his keep by playing all kinds of roles, from carnival barker to clown to contortionist. His magnum opus was his role as “The Hypnotic Living Corpse,” wherein he would be buried alive in front of an audience and then “resurrected” 24 or even 48 hours later, surviving underground through a ventilation system and a diet of malted milk balls. What a way to make a living.

****I’m not so naive as to think that the executives at a movie studio suddenly grew a conscience and decided to “do the right thing” without angling at some sort of financial incentive. But at least they didn’t double down on the gross parts.

*****Did all of the 19th century Tods spell their name with one “d”? What’s going on there?

Freaks is now streaming on HBO Max, and it is available to rent elsewhere.

*****First of all w in the actual f?! now I need to watch this.

Secondly, Tods of the world rise up, Jeremy is Not The Boss of You!