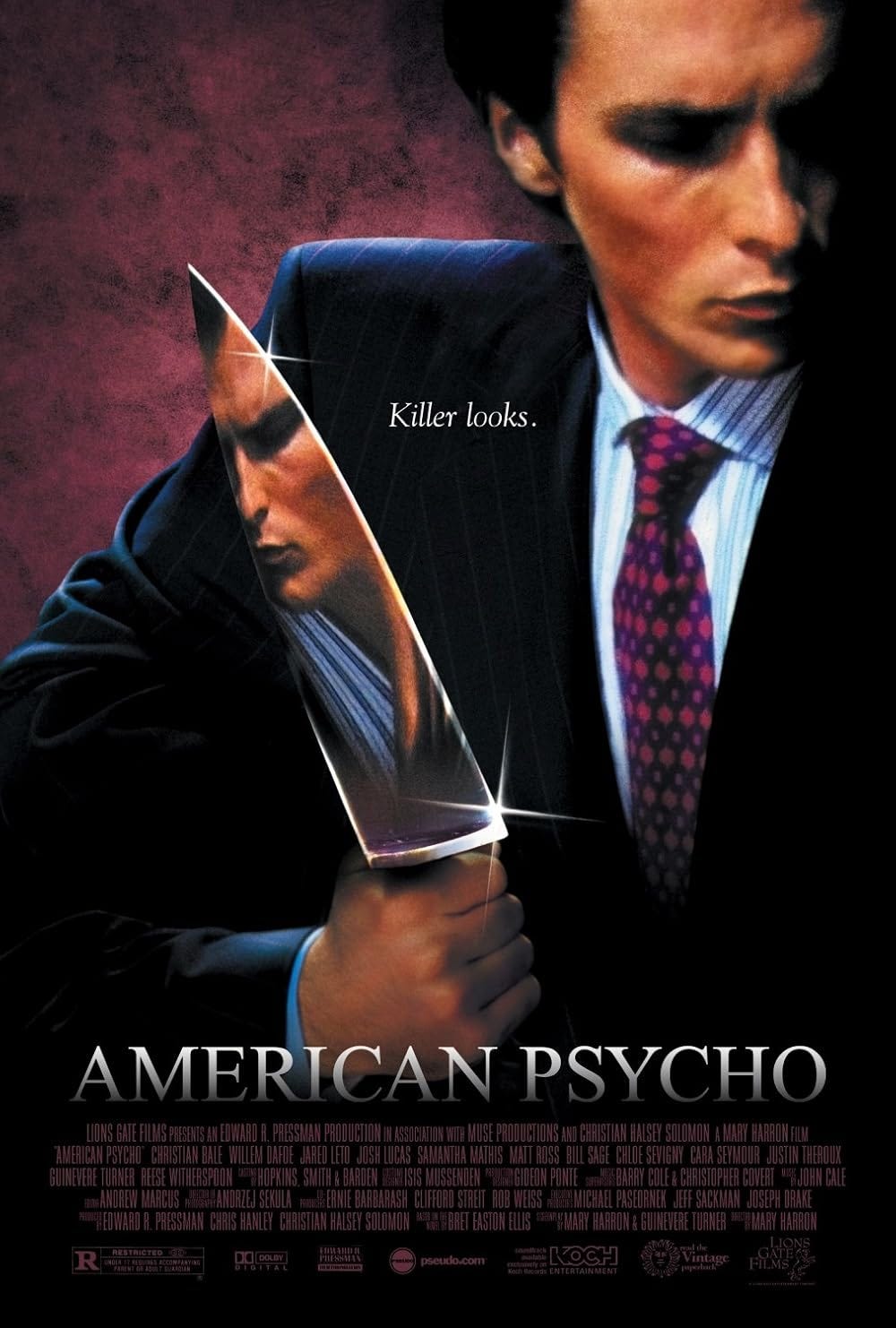

Guest post alert! Today’s newsletter was written by the incomparable Kitty Byrge, the chief champion of all things horror in the Rocket City—she’s the brains behind Hello Huntsville Horror, in fact. But today you need to know about the Hauntsville Film Fest, the only woman-run horror film festival in the Southeast. Kitty put together a great slate last year for the festival’s inaugural weekend, bringing in more than 500 people over two days at the Orion Amphitheater, and she outdid herself this year by committing to programming both classic and new films that are directed, produced, or written by female, female-presenting, and non-binary filmmakers. One of the Friday night features happens to be American Psycho, a film that Kitty has researched heavily, as you’re about to learn. Hauntsville goes down November 1 & 2, and it’s free(!), so come watch American Psycho and some other great films at Campus No. 805—after you read this newsletter, of course. Take it away, Kitty!

“Hi, get ready with me!” #GRWM

“My name is Patrick Bateman. I’m 27 years old. I believe in taking care of myself and a balanced diet and rigorous exercise routine. In the morning, if my face is a little puffy, I’ll put on an ice pack while doing stomach crunches. …After I remove the ice pack, I use a deep pore cleanser lotion. In the shower, I use a water-activated gel cleanser, then a honey almond body scrub, and on the face, an exfoliating gel scrub. Then I apply an herb-mint facial mask. …Then moisturizer, then an anti-aging eye balm, followed by a final moisturizing protective lotion.”

The camera pans over Patrick Bateman’s Instagram-ready apartment. Stylized and trendy but jarringly cold and hollow. His extreme, neurotic focus on fitness and skincare, along with his disassociation from his public character, reflects the experience of many women who are socially pressured to perform their femininity.

The opening monologue of American Psycho illustrates John Berger's theory of the "male gaze," which holds that women constantly play for an unseen audience by learning to see themselves through men's eyes. Bateman, despite being male, is likewise caught in a loop of performance and is never able to completely break free from the persona he presents to the outside world.

Surprisingly, Bateman—a racist, homophobic, misogynistic, yuppie Wall Street serial killer—has emerged as a figurehead for two extraordinarily different groups: hyper-masculine “sigma males” and the self-identified “feral coquettes” or “free girls.” Why does such a character permeated in toxic masculinity resonate with female audiences?

TikTok girls declare “He’s just like me!” Neurotic performative behaviors, over-the-top beauty and fitness routines, detached internal monologues, outward masking of internal emptiness. Sound familiar? Meanwhile, film bros idolize his toxic traits: narcissism, misogyny, violence, control. Many of them fail to recognize the film’s satirical critique of those traits. These different interpretations further reflect misunderstandings between femininity and masculinity.

Bateman’s excruciatingly normal yet luxurious existence is just a routine of obsessive research to allow Bateman to assimilate into Manhattan socialite crowds. The film focuses on the absurdity of his everyday life and less on his explicit violence. Bateman is not a symbol of masculinity and power but rather a product of capitalism, consumerism, and a patriarchal society. American Psycho is a satirical portrayal of male vanity and competition that critiques masculinity more than glorifies it.

Patrick Bateman has an obsession with status symbols, even down to his “bone-colored” business card. He dines in the chicest New York City restaurants, wears the trendiest designer fashions, and purchases the most top-of-the-line electronics. And he reduces people down to the clothing they wear, erasing humanity to a label.

The 1980s setting is dominated by a consumer-driven culture, but it also resonates with current audiences—specifically women who are subjected to similar societal pressures to conform to certain aesthetics and standards. American Psycho satirizes the notion that outward appearance and material success are markers of worth in society, yet women today are still frequently scrutinized on their looks and abilities to perform traditional feminine tasks.

As Bateman and his colleagues like to say, “There are no girls with good personalities.” Modern opinions of Bateman’s violent misogyny reflect real-world gender dynamics. Small and casual sexist remarks can lead to more dangerous expressions of misogyny that escalate to actual violence against women. This phenomenon is being observed all over the internet, predominantly in the “manosphere.” “Hustle culture,” which cites Bateman as a hero, celebrates male wealth created specifically by hard work, self-discipline, fitness, and grooming.* Bateman is even a foundational fixture of an entire subgenre: the “cause for concern” film.** The objectification, rejection, and ultimately disposal of women are shown as extremes here, but they’re actually devastating reflections of a societal norm that views women as consumable objects.

Bateman’s masculinity is not only toxic but inherently fragile. He dominates women, sexually and violently, as a way to validate his own masculinity, which is continually under threat from a society that values wealth, power, control, and status. His sexual encounters highlight his narcissism and focus on self-affirmation, not desire. When he strips sex workers of their identities before assaulting them, he’s acting out the stripping of his own identity that occurs when he’s frequently mistaken for other men. He’s also deeply uncomfortable with any scenario that strays from his hyper-masculine persona, especially affection or admiration from men. He’s constantly teetering on the edge of internalized repression and homophobia. His masculinity itself is a performance.

Bret Easton Ellis’s original novel was extremely controversial, called “obscene” and “a how-to novel on the torture and dismemberment of women.” It includes extreme descriptions of violence and depicts scenes of sexualized assault and sadism. Feminist director Mary Harron and her queer cowriter Guinevere Turner focused instead on the protagonist’s vanity, transforming the novel into a powerful piece of feminist cinema.*** Patrick Bateman is both a product of and a victim to the flaws of hyper-masculinity and the roles of gender in a capitalist society, and yet women see him as a reflection of their own struggles with collective expectations. Harron’s and Turner’s feminist perspective reframed American Psycho as a satire that critiques not only men but the structures of performance, consumption, and power that oppress all genders.

*Another hustle culture “hero,” Andrew Tate, began online with casual sexist remarks. He’s now awaiting trial in Romania on human trafficking and rape charges.

**If you’re on a date and he tells you that his favorite films include Fight Club, American Psycho, A Clockwork Orange, or The Wolf of Wall Street, ask for the check.

***Roger Ebert had this to say in a positive review: “It’s just as well a woman directed American Psycho. …She’s transformed a novel about bloodlust into a movie about men’s vanity.”

American Psycho is now streaming on Netflix and Paramount+, and it is available to rent elsewhere.

It's interesting how American Psycho's rep keeps changing, especially how pragmatic changes between the book and movie are now seen as symbolic and not because the book is borderline unfilmable. But I agree that the above interpretation makes sense.

I would add, though, that the gender angle was not the intent of the work. It's an overall social commentary, done in the tradition of Notes From The Underground, and (I suspect) influenced deeply by Barbarians At The Gate.

However, the movie is very different to the book in several aspects and I can totally see other symbolisms arise. It's just the nature of adapting what is a complex novel that isn't interested in wooing its audience (just like Notes). Though I disagree that the novel or movie was an analysis of the male gaze. I think that's something imposed by the audience (though that then still makes it a relevant symbolism).

I'm a bit shocked though that some groups idolise Bateman. Now that is totally missing the point of the work. Like people who fixate on the Brass Balls speech in Glengarry Glenn Ross. If you think Bateman should be a role model, you really need to check your values.

The book and the movie aren't that different: they're both a depiction of the numbing shallowness of Wall Street life and the imagined escapism that ensued in the head of Bateman. Now if you'll excuse me, I've got to return some video tapes.